A Brief History of Chinese Painting

Chinese Painting

Chinese painting is one of the oldest, continuous artistic traditions in the world. Their traditional style involves the same techniques as calligraphy with a brush dipped in black or coloured ink, without the use of oils.

In early Imperial times (Jin Dynasty 265 – 400), calligraphy and painting were the most highly appreciated arts in court circles and were produced almost exclusively by amateurs, often aristocrats and scholars, who had the leisure time to perfect their techniques. During the Jin Dynasty, critics began to write about art and individual artists started to emerge.

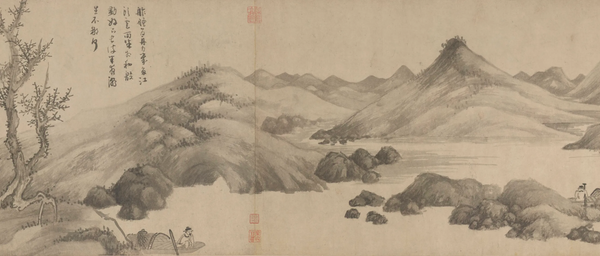

In the subsequent Tang Dynasty, figure painting flourished at the royal courts and reached the height of elegant realism, comprising outlining in fine black ink lines with freely painted brushstrokes of colour and elaborate detail. Many paintings were landscapes, often monochromatic and sparse, the purpose was not to reproduce exactly the appearance of nature but rather to grasp an emotion or atmosphere so as to catch the ‘rhythm’ of nature.

Landscapes of more subtle expression appeared in the Song and Yuan Dynasties (960-1368), with distance conveyed using blurred outlines, mountain contours disappearing into the mist and emphasis placed on the spiritual qualities of the painting. Painters then joined the arts of poetry and calligraphy, the three arts worked together to express the artist’s feeling more completely than one could do alone.

Beginning in the 13th Century, more narrative painting developed with a wider colour range and busier compositions. During the early Qing Dynasty (16-44-1911), painters known as individualists rebelled against many of the traditional rules of painting and found ways to express themselves more directly through free brushwork.

In the 1700’s and 1800’s, great commercial cities such as Yangzhou and Shanghai became art centres where wealthy patrons encouraged artists to produce bold new works. In the late 1800s and 1900s, Chinese painters were increasingly exposed to Western art. Some that studied in Europe rejected Chinese painting whilst others tried to combine the best of both traditions.

Qi Baishi was one of the most renowned painters of this time, beginning life as a peasant and becoming a great master. His best known works depict flowers and animals.

Chinese Wallpaper

Chinese wallpaper seems to have developed out of the European taste for Chinese pictures, the East India companies shipping goods across the globe and the ability of Chinese workshops to respond to Western demand. A trickle of Chinese pictures and prints accompanied goods from China such as tea and raw silk, with Chinese screens and hangings beginning to appear in European royal residences. In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Oriental objects and materials became part of grand European interiors in many stately homes with Chinese pictures hung as framed works of art. These often appeared in the more feminine areas of a household such as bedrooms, dressing rooms and drawing rooms.

The strong demand for sets of pictures to be used as wall decoration eventually ignited the development of Chinese wallpaper with drops specifically made to decorate the entire wall surface of a room. Outlines of the designs were either printed or painted by hand. In contrast to the Chinese porcelain produced for export which was often decorated with western motifs, Chinese wallpaper retained its indigenous Chinese imagery. Many were adorned with flowering trees and plants, birds, insects and rocks, representing idealized evocations of Chinese gardens. This kind of scenery appeared around 1750 and was produced continuously until the second half of the 19th century.

A smaller group of Chinese wallpapers were decorated with human figures shown in landscape settings shown in agricultural, manufacturing and other activities. Often celebrating the production of rice, silk and porcelain, these tended to be more expensive as they were more labour-intensive to produce.

The popularity of this wallpaper for westerners was its sheer visual beauty and technical finesse, coupled with the high esteem China was held in 18th century Britain as a country that combined ancient virtue with modern commerce. The exotic, foreign scenery depicted in the papers also played a role in their desirability.

Chinese wallpaper entered Britain via London, delivered by the East India Company’s ships. The papers were then auctioned at East India House either to private individuals or through shops in London.

The popularity of ‘chinoiserie’, as it is now known, continues.

Close

Close